Tobacco companies manipulate the filters of tailor-made cigarettes in ways that make the toxic smoke feel less harmful than it really is, making it possible for you to inhale cancer-causing chemicals. This is the con that kills.

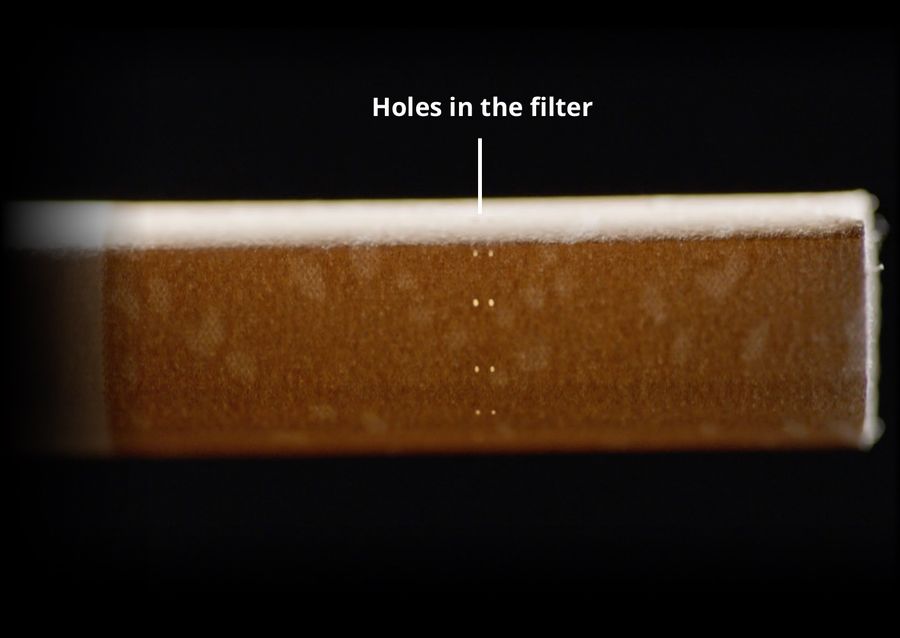

Tiny holes are added around the filter paper to make the smoke feel lighter…but it is just as harmful.

Tailor-made cigarettes can have tiny holes in the paper around the filter. This is known as filter ventilation. When the smoker draws on the cigarette, air enters through these tiny holes and mixes with the smoke.1

The diluted smoke feels lighter in the mouth, throat and lungs.

While it is tempting to believe the lighter-feeling smoke may be less harmful,2, 3 it is not.

Lighter-feeling smoke is just as harmful

The same signs of smoking-related damage are found inside the bodies of people who smoke cigarettes with high level of filter ventilation and people who smoke cigarettes with very little filter ventilation.4

This is because when the smoke is diluted with air it contains less nicotine,1 the addictive substance in tobacco.5, 6 So to get the nicotine ‘hit’ they need, people who smoke these filter ventilated cigarettes tend to inhale a larger volume of smoke overall by:

- covering up some of the holes with their fingers and mouth

- smoking harder or more often

- smoking more cigarettes.1

Some people know that they do these things. Others are not aware that this is the way they smoke.

As a result, people who smoke highly ventilated cigarettes end up taking in a larger volume of smoke overall.7 This means they end up inhaling at least as many harmful chemicals as they would if they were smoking cigarettes with little or no filter ventilation.

Which cigarettes contain tiny holes in the filter?

Filter ventilation is the main way in which differences in the strength of taste of Australian tailor-made cigarettes are achieved.8

Some people who smoke may remember when tobacco companies used the words ‘light’ and ‘mild’ to describe different cigarette varieties. Now they use different colours and other descriptions. Cigarette varieties with the most filter ventilation are usually those named with lighter colours such as white, grey or silver. At the other extreme, varieties named with darker colours such as red usually have very little or no ventilation and so have a stronger taste. Other colours like gold and blue are in between.9

One study estimated that about 90% of Australian cigarette brands use filter ventilation.8

What about rollies?

Many filters for making roll-your-own cigarettes don’t have filter ventilation holes. But tobacco companies make the toxic smoke from roll-your-own tobacco feel lighter or smoother by mixing in additives that mask the harshness of the smoke.10-12

Additives make the smoke feel less harmful than it is

Tailor-made cigarettes also contain additives to hide the toxic smoke’s true harshness and make it feel less harmful than it is. If the tobacco didn’t have additives in it, the smoke would be so strong and harsh on the throat that few people could inhale it.13

By reducing the feeling of harshness, additives make it easier to breathe in the toxic smoke. It doesn’t feel as damaging to the airways as it really is. This allows you to keep taking in lungfuls of toxic cancer-causing chemicals.13

Some of the additives that mask the harshness of the smoke include:

- Humectants: when they burn, some humectants produce toxic substances like acrolein and propylene oxide that can weaken your immune system, cause serious heart damage and disease, or cause cancer.14-16

- Flavour additives: mask the true taste of the smoke. While most flavour additives are safe to eat, all the additives in tobacco are burned. Burning changes many of them into toxic chemicals. The lungs are more likely to be damaged by these chemicals.17

- Menthol: a small amount of menthol is added to many varieties of tobacco,18 so menthol can be found in cigarettes that do not taste like menthol.

No matter what they do to it, you’re inhaling the same toxic poisons

Some of the toxic poisons in cigarette smoke are created when the additives are burned.

Many of the harmful chemicals in the smoke are created when the tobacco is burned.19

So it doesn’t matter what colour variety of cigarettes you smoke, or how light or smooth the smoke from your cigarettes might feel – all tobacco smoke contains over 200 toxic poisons.20-28

Escape the con

Tailor-made cigarettes are manipulated in ways that hide just how harsh and painful the toxic smoke really is. By reducing the feeling of harshness, additives make it easier to breathe in the toxic smoke. It doesn’t feel as damaging to the airways as it really is. This allows you to keep taking in lungfuls of cancer-causing chemicals.

The best way to escape this con is to quit smoking.

Frequently asked questions

What about heated tobacco products?

All forms of tobacco are harmful. The aerosol from heated cigarettes, also known as heat-not-burn, contains many of the same poisonous cancer-causing chemicals as cigarette smoke...

What about vapes?

While vapes don’t contain tobacco, they do contain hundreds of chemicals: some are known to be harmful to inhale and many haven’t been tested at all. Most e-vapes contain nicotine, which is highly addictive. People who vape are more likely to go on to smoke than people who don’t vape...

Do you know how many chemicals are in tobacco smoke and how they get there?

All tobacco products are harmful. Tobacco smoke contains over 7,000 different chemicals. More than 200 of these chemicals are poisonous, released when the tobacco is burned. At least 69 are known to cause cancer. It doesn’t matter what tobacco product you use, or what the smoke tastes or feels like – all tobacco smoke is toxic to your body.

References

- Winnall WR and Scollo M. 12.8 Construction of cigarettes and cigarette filters, https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-12-tobacco-products/12-8-construction-of-cigarettes-and-cigarette-filters (2022, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- Mutti S, Hammond D, Borland R, et al. Beyond light and mild: cigarette brand descriptors and perceptions of risk in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction 2011; 106: 1166-1175.

- Elton-Marshall T, Fong GT, Yong H-H, et al. Smokers’ sensory beliefs mediate the relation between smoking a ‘light/low tar’ cigarette and perceptions of harm. Tob Control 2015; 24: iv21-iv27.

- Carroll DM, Stepanov I, O'Connor R, et al. Impact of cigarette filter ventilation on U.S. smokers' perceptions and biomarkers of exposure and potential harm. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 2020: cebp.0852.2020.

- Edwards G, Arif A and Hadgson R. Nomenclature and classification of drug-and alcohol-related problems: a WHO memorandum. Bull World Health Organ 1981; 59: 225–242.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatry Association, 2013.

- Kozlowski LT and O'Connor RJ. Cigarette filter ventilation is a defective design because of misleading taste, bigger puffs, and blocked vents. Tob Control 2002; 11: i40-i50.

- King B and Borland R. The "low-tar" strategy and the changing construction of Australian cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res 2004; 6: 85-94.

- Winnall WR, King B and Scollo M. 12.9 Labelling of tobacco products in Australia, https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-12-tobacco-products/12-9-labelling-of-tobacco-products-in-australia (2022, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. How tobacco smoke causes disease: the biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease. A report of the Surgeon General. 2010. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

- Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR). Tobacco additives, https://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/opinions_layman/tobacco/en/about.htm#7 (2010, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation (TobReg). Report on the scientific basis of tobacco product regulation: fifth report of a WHO Study Group, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/161512/9789241209892.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (2015, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- Winnall WR. 12.6 Additives and flavourings in tobacco products, https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-12-tobacco-products/12-6-additives-and-flavourings-in-tobacco-products (2022, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM). Additives in tobacco products: glycerol, www.rivm.nl/documenten/additives-in-tobacco-products-glycerol (2012, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- Henning RJ, Johnson GT, Coyle JP, et al. Acrolein can cause cardiovascular disease: a review. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2017; 17: 227-236.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Volume 60: Some industrial chemicals. Propylene oxide., http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol60/mono60-69.pdf (1994, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR). Final opinion on additives used in tobacco products, http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/emerging/docs/scenihr_o_051.pdf (2016, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation (TobReg). Advisory note: Banning menthol in tobacco products, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/205928/1/9789241510332_eng.pdf (2016, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- Winnall WR. 12.4 Emissions from tobacco products, https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-12-tobacco-products/12-4-emissions-from-tobacco-products (2022, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- National Toxicology Program. Report on carcinogens, 9th edition. 1999. US Department of Health and Human Services.

- National Toxicology Program. Report on carcinogens, 15th edition. 2021. US Department of Health and Human Services.

- National Toxicology Program. NTP Report on carcinogens background document for environmental tobacco smoke. 1998. US Department of Health and Human Services.

- National Toxicology Program. NTP Report on carcinogens background document for tobacco smoking, Final March 1999. 1999. US Department of Health and Human Services.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General. 2006. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Biomonitoring Program. Tobacco., https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/tobacco.html (2022, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- World Health Organization. The tobacco body, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-PND-19.1 (2022, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- NIH National Cancer Institute. Harms of cigarette smoking and health benefits of quitting, https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/tobacco/cessation-fact-sheet#r1 (2022, accessed 19 Sep 2022).

- Australian Government Department of Health. What is smoking and tobacco?, https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/smoking-and-tobacco/about-smoking-and-tobacco/what-is-smoking-and-tobacco (2022, accessed 19 Sep 2022).